Our feelings shape our daily lives. But the words we use to describe them, and the ways we express and understand them, differ across cultures and through time.

Our exhibition at the RCN Library and Heritage Centre draws on new research from the Queen Mary Centre for the History of Emotions. We invite you to explore the emotions expected of nurses through time, and the different experiences of caregivers themselves. Join us in this online version as we delve into a range of feelings - from anger to reflection, sadness to compassion, fortitude to fear - and question how emotions feature in care. Who is ultimately responsible for them?

It’s not just the way we understand emotions that changes through history, but our experiences and feelings themselves. This has important implications for nursing. Care has been linked to emotional traits, for good or bad, since at least the 1850s. A nurse’s character, unlike a doctor’s, was held up as more important than their skills and abilities. While at times this may have improved care, this link has also reinforced damaging stereotypes about nursing and gender, class, religion or race.

For more information on this topic, why not have a look at our reading list.

Motherly Hearts

Sister. Matron. Midwife. Ideas about women have long shaped the image of the nurse. Early nursing education and training drew on domestic values. Nursing was seen as preparation for a woman’s role as wife and mother, with maternal instincts seen as essential for care.

Until the Second World War, a ‘marriage bar’ meant women typically stopped working when they got married. For those who did not marry, nursing was still framed as meeting the biological drive of motherhood. This began to change in the 1950s. Nursing became increasingly seen as a career and less emphasis was placed on mothering instincts. Instead, nurses were expected to show love for the profession. And yet this history continues to a affect nursing today: nearly 90% of nurses in the UK are female.

In 1918, the Mothercraft Training Centre opened in Earl’s Court, London. Based on practices in New Zealand, mothercraft taught young women to be good mothers and raise healthy babies. Trained nurses taught these skills across the empire.

But who for? Mothercraft was rooted in the prejudice that working-class women were ignorant.

A good death

In the nineteenth century, grief could be seen as damaging to physical health. A cheerful nurse might even save a patient’s life.

In health care, death is part of the day to day. As well as offering emotional and practical support, nurses carry out clinical tasks from infection prevention to last offices. Often these methodical practices provide a welcome ritual through which to channel the emotions that come with sad and stressful times.

Yet death and dying does not always have to mean sadness. Nurses might feel anger and frustration at losses that could have been prevented. They may feel relief at an end to suffering. End of life care can also be an opportunity for connection with patients and their families.

Death can also conjure unexpected emotions. Well known for their dark humour, nurses tell stories of laughter cropping up in the most unlikely places.

Hospital Romance

This attitude to nursing was new after the Second World War. Victorian matrons had fiercely protected their probationers from the attentions of doctors. Later, between the wars, the General Nursing Council debated “purifying the profession” and removing nurses from the register for sex outside marriage.

Doctor-Nurse romances were a popular post-war Mills & Boon sub-genre. Most authors were, or had been, nurses. This proved important, since what contemporary readers demanded more of was not sex but details of clinical practice.

In the swinging sixties, nurses were newly presented as sexually available, not only in Carry On films but in NHS recruitment campaigns too.

From double standards to sexual harassment, what impact have these stereotypes had on nursing?

Emotions under fire

War is one of the most challenging working environments for any nurse.

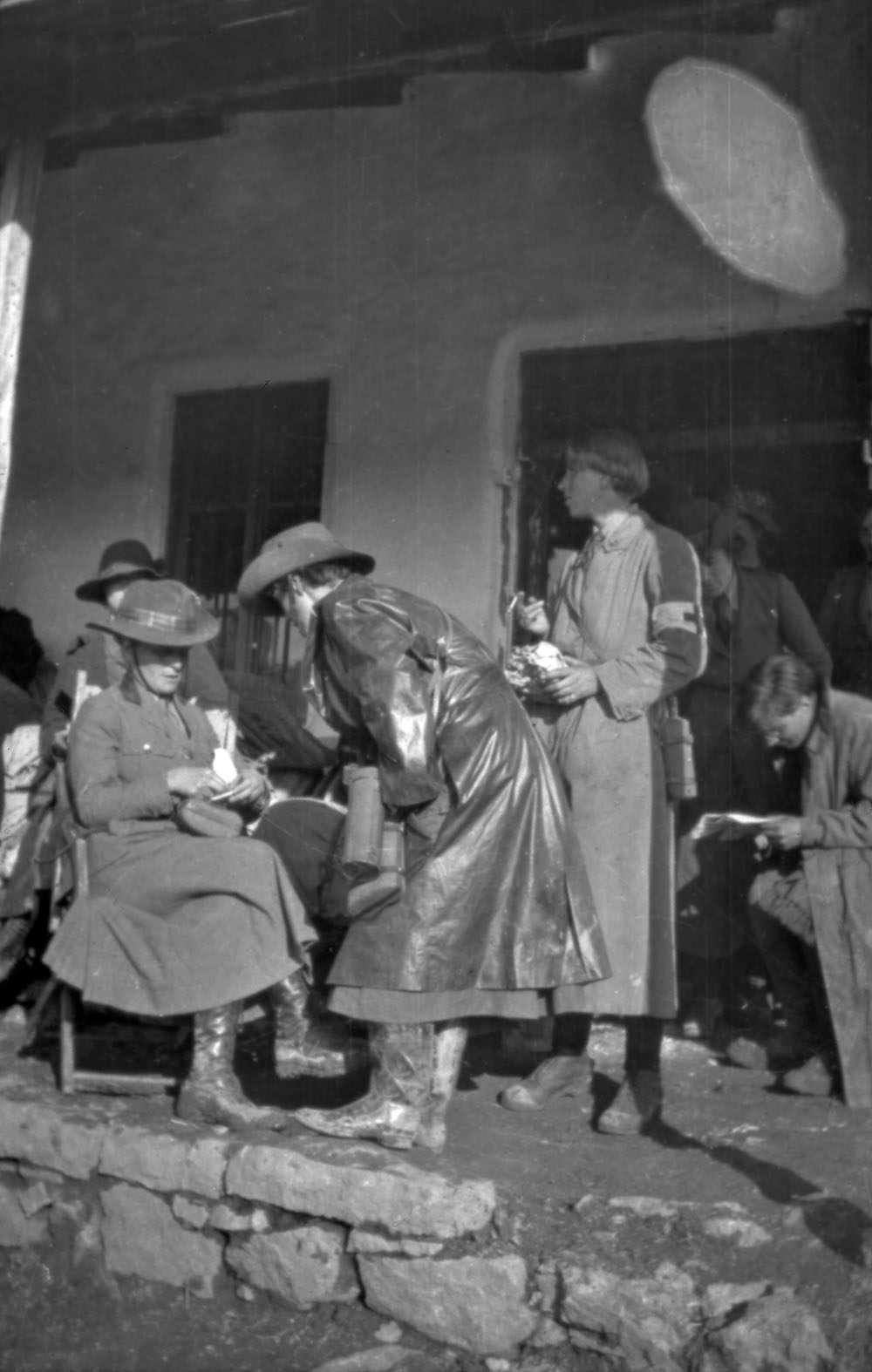

The propaganda surrounding nursing in the First World War showed a particular kind of nurse. This was a woman who demonstrated fortitude, self-sacrifice and remained cheerful when faced with danger and crises.

The reality was very different. Many nurses experienced shell shock during the conflict, which often went unreported and uncared for. The expectation on nurses to be resilient remains, despite short-sta ffing and a lack of resources. How can we better recognise these limits? Who should provide the space needed for self care?

The images below are from the RCN’s collection of lantern slides showing candid snapshots, capturing some of the harsher realities of nursing at war. These unique images present a different reality to the propaganda surrounding nursing at this time, as seen in the photographs of posed nursing staff.

Faith in Nursing

Nursing has been closely linked to religious orders since the Middle Ages. These still trained nurses into the twentieth century. Icons like Florence Nightingale and Edith Cavell emphasised the religious drive of their calling, looking to the bible and prayer books for advice and emotional support.

After the First World War, this devotional side to healthcare became seen as old-fashioned. Yet hospital schools still required nurses to attend daily prayers until at least 1950, sometimes conflicting with a training that emphasised practical and scientific skills.

Faith can have a range of meanings in health, from religion to belief in science or the NHS. So where exactly should we place our faith today?

Listen to the oral history of Sirima Bandara talking about her faith. Born in Sri Lanka in 1947 into a middle class Buddhist family where the girls were well educated. She came to the UK aged 28 and trained as a nurse in London. Here she talks about the influence of various religious practices on her life and health (Audio duration 1m).

Radical Nurses

When things go wrong, who can nurses turn to?

In the early twentieth century membership of a trade union was frowned upon in nursing. Middle class matrons saw nursing as a vocation, not a trade. With limited support, nurses turned to each other, channelling their anger and frustration into collective action.

In 1937, masked nurses marched through central London, calling for higher pay and a 48-hour-week.The masks protected these nurses from blame – from their peers as well as their bosses. At the time, the RCN and most nursing journals did not support the campaign, thinking a 48-hour-week would create a nursing shortage.

The Radical Nurses Group was established in 1980. Members of the group felt frustrated with the level of care they were able to provide. Through a nationwide network of support groups, they hosted meetings to foster collective opportunities for change.

Yet nurses’ rights are fundamental to patient care. Today, the RCN’s campaign for safe staffing levels calls for a law on the minimum number of nurses required across UK health care settings.

So who should care? Is it the individual nurse, the institution, the patient or the government?